16 Principles for Cycleway Network Planning

London is a great place to learn about planning cycle infrastructure Because it has made many mistakes and because of its recent success. It has learned what to do and what not to do. Drawn from London’s 84 years of building cycle facilities, and my own 45 years of using them, the video, above, recommends 16 principles on which to base cycleway network planning. To help planners assess their validity, statements of the 16 principles are followed, in the video, with ironical statements of the 16 converse principles. When cycle infrastructure projects are put to consultation they usually attract majority support. But they also encounter bitter opposition from taxi drivers and from car drivers who rely on private vehicles. Cycle planners need to appreciate both sides of the argument. Here are the 16 recommended principles for cycleway planning:

- Set the level of investment in cycle infrastructure to match the target mode share (eg allocate 1% of the transport budget to cycling to achieve a mode share of 1%, or 20% to achieve a mode share of 20%). Cycleway networks are a highly cost-effective way of investing in the public goods of transport, leisure, health, amenity and sustainability. A modal shift to cycling makes roads less congested. The UK Department for Transport, puts the average benefit-cost ratio (BCR) for investment in cycling at 5.5:1, which is approaching three times the typical 2:1 ratio for approving investments in public transport. Compared to powered transport, cycleway maintenance costs are imperceptible. So when the target mode share has been achieved investment levels can return to present levels.

- Invest in both commuter and leisure cycleways. They are equally important; they attract similar user numbers; the two cycleway types can work together.

- Give commuter cyclists the shortest possible direct links between significant origins and significant destinations. This principle applies both at the local scale and the city scale.

- Give leisure cyclists both loops and trails. If the scenic quality of a cycleway is high, commuters may choose to use leisure facilities in preference to shorter A-to-B routes for getting to work.

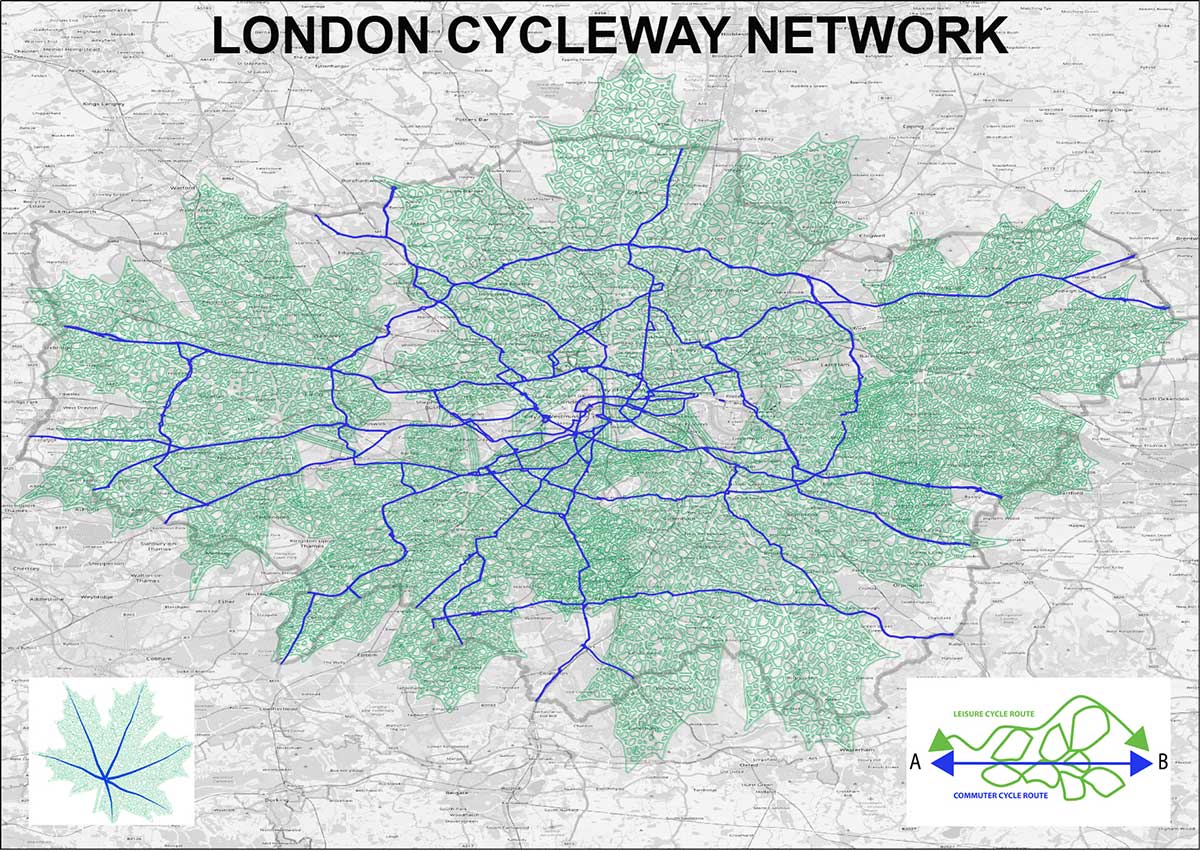

- Use leaf and branch network patterns for cycleways. Trees are transport systems and leaf-patterns work well for cycleway network planning. The loops facilitate journeys to shops, stations, parks, hospitals and other destinations.

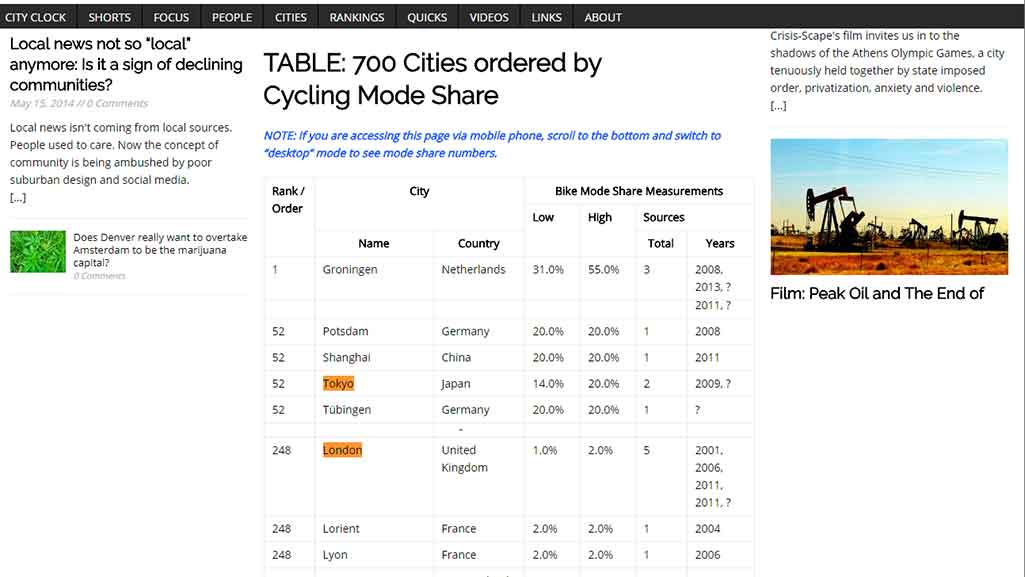

- Large cities should emulate and then surpass the cycling mode share of Tokyo, which is the World’s Largest Metropolitan Area. The table shows London with a mode share of 2% and Tokyo with 20%. At the city scale, size need not limit the cycling mode share.

- Use the principle of filtered permeability to make cycling the quickest transport mode for trips up to at least 5 km. Closing minor roads to non-cycle through traffic is a city-friendly policy.

- Do not conceive, plan or design cycleways as ‘mini-roads’ and do not plan them to run beside ‘maxi-roads’, except as a last resort. Remember that cycling is different.

- Plan cycleways, instead of cycle routes, and do not use road signs or road markings to attract cyclists to dangerous routes.

- Relate the width of cycleways both to predicted traffic volumes and to aesthetic considerations. Breadth and narrowness are scenic qualities. Well-mannered cyclists are happy to slow down or walk when near pedestrians.

- Every cycleway should be a context-sensitive design, even if some use of design codes is necessary.

- Design different types of bikeway for different categories of bike user (in tems of widths, surfacings, gradients etc). The cyclists have different preferences and their bikes have different tyres.

- Use standard horizontal curves and vertical curves only for the busiest and fastest cycle tracks. Remember that some cyclists are less able-bodied than others.

- Design most cycleways as greenways, in the sense of being ‘multi-objective routes that are good from an environmental point of view’. Not all greenways are within sight of vegetation.

- Instruct landscape architects to work with local cycling groups and with transport engineers to plan and design cycleways that, as well as being functional, have better scenery and a much better user experience than current world norms.

- Brief design teams to create cycleways that flow through the city, a source of joy and health to all who use them. Let urban landscapes billow across cycleways, revealing the city’s treasures.

See also:

- Lecture on London cycleway planning

- History of London cycleway planning

- Benefit Cost Ratio BCR for cycle infrastructure investment

- 18 videos on London cycleway planning

How the London Principles would work in London

The GLA, the City Corporation and the 32 boroughs need to work with specialised agencies, trusts, charities, societies and local cycling groups to develop a comprehensive cycleway network for commuter and leisure use. Transport for London has taken a lead by creating cycle superhighways on the Transport for London Road Network (TLRN). TfL maps its 360 miles of road in red and calls them ‘red routes’. With cycle superhighways being built along them, they are becoming ‘red and green routes’. TflL maps cycle superhighways in blue. The above plan shows the TLRN in blue to indicate its default accommodation of segregated cycle lanes (where more direct routes are unavailable). Local cycleway loops are indicated in green. Their routes can include filtered residential roads, greenways, green streets, garden streets, pedestrianised high streets, park routes, safe routes to school, reservoir walks, river walks and canal walks. Shared walking-cycling routes work well, providing pedestrians have ethical and legal priority.

The cost of 180 miles of cycle superhighway routes has been estimated at £3.24 bn and, using the DfT Benefit:Cost Ratio of 5.5:1 the benefit would be £17.8bn (using a cost of £12.5 million/mile for cycle superhighways: see Note 3).