Landscape, Townscape and Seascape Character Assessment

LI London held a meeting about Character Assessment on 28.11.2016. It was chaired by Robert Holden and the speakers were Christine Tudor (Natural England) Chris Drake (Kent County Council), Jon Rooney (AECOM) and Ben Croot (LDA Design). Having given the subject little thought for 20 years, I found the evening interesting and enjoyable.

Natural England has given welcome support to the development of landscape character assessment for many years. It’s website states that: ‘We’re the government’s adviser for the natural environment in England, helping to protect England’s nature and landscapes for people to enjoy and for the services they provide’. Given its statutory role, NE’s descriptive approach to landscape assessment is proper. But landscape architects need to go further. We have, or should have, a central role in the protection, conservation and enhancement of the natural and built environment for the public benefit. As well as description, this requires evaluation.

Landscape Assessment began as a qualitative approach, It can be traced back to task of selecting the post-1947 UK National Parks and defining their boundaries. This was done by expert judgement. Similarly, when the oil industry ‘hit’ Scotland in the 1970s a qualitative assessment of potential sites for construction yards was necessary. David Skinner, then teaching at Heriot-Watt University, was given one of the best commissions a landscape architect can ever have had. He was asked to walk those parts of the Scottish coast he had not already walked and to make qualitative assessments. Remembering this background, I asked the speakers a question (which can be heard in the last few minutes of the above video): ‘How is the evaluative component dealt with under the current assessment system?’

The answer, I believe, is that it has been dropped. It was in the 2002 Assessment Guidelines but it is there no more. This is a pity. I think of an ‘assessment’ as something which requires professional judgement and is categorically distinct from ‘description’ however much professional expertise is deployed in both tasks. To use a medical analogy, it resembles the distinction between diagnosis and treatment. A radiologist can describe what is wrong with a limb. It requires a physician to evaluate which treatment is most likely to be successful. The skills are distinct but related.

Geoffrey Jellicoe was asked to advise on the siting of an oil platform yard in a location with high scenic quality: Loch Kishorn, in Scotland’s west highlands. The commission may have resulted from Skinner’s work or from a similar planning application on the other side of the Loch, which had been rejected. In either case, the significant point is that Kishorn was recognised as an area of high scenic quality and high sensitivity. The advice Jellicoe gave on Kishorn was excellent and should have been followed in detail.

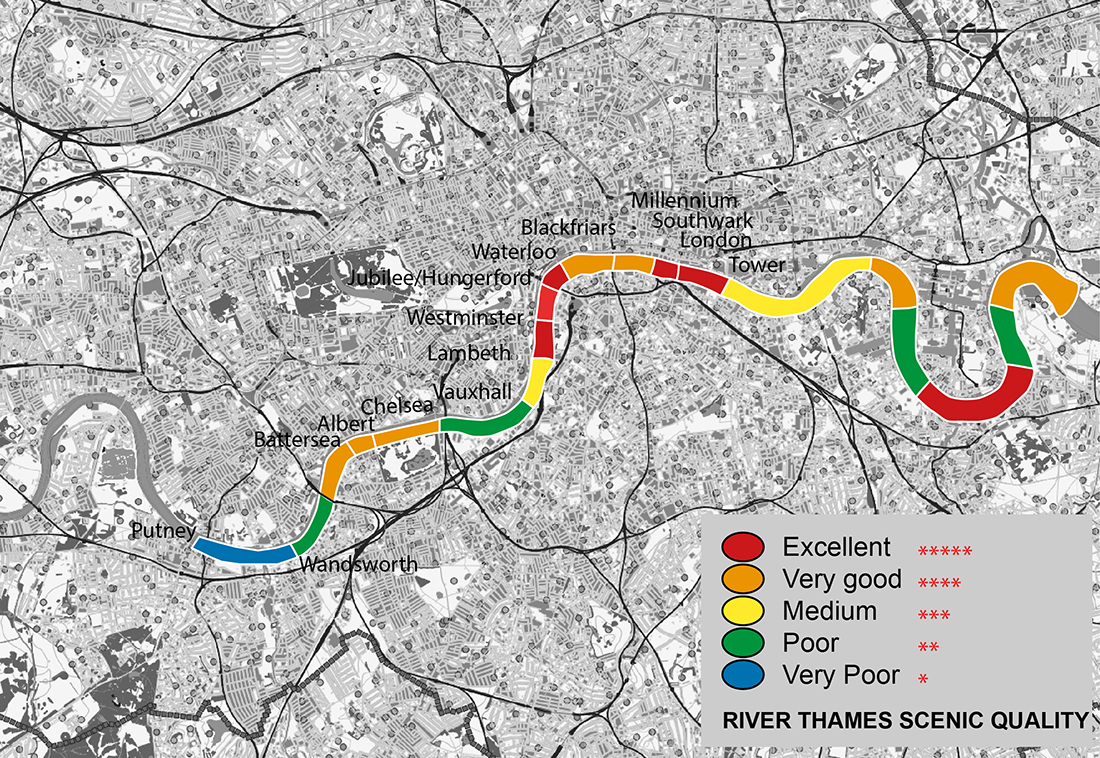

Robert Holden and I undertook a landscape scenic quality assessment of the proposed site of London’s garden bridge. We concluded that King’s Reach has some of the highest scenic quality in Central London and that an alternative site for the Garden Bridge should be found. If the bridge is not built, as seems perfectly possible, our reaction may be ‘we told you so’.