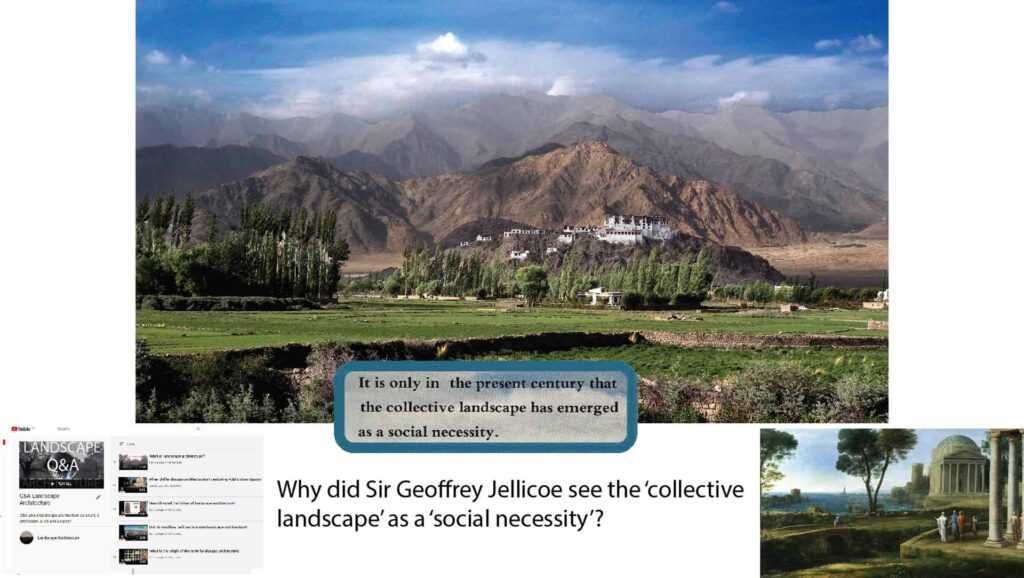

What is the Collective Landscape Q&A

Short answer: ‘It is only in the present century that the collective landscape has emerged as a social necessity’ (Geoffrey Jellicoe, The Landscape of Man, 1975). Jellicoe was inspired by Carl Gustav Jung’s concept of the Collective Unconscious and, it seems, used the term Collective Landscape to describe the landscape architecture and landscape planning goal of creating a community landscapes for the world.

Longer answer: In town and in country our society needs landscapes where people can walk in safety, pick fruit, cycle, work, sleep, swim, listen to the birds, bask in the sun, run through the trees and laze beside cool waters. Some places should be busy. Other places should be solitary.

Rivers should be prized out of their concrete coffins and foul ditches.

Quarries should be planned as new landscapes.

Forests should provide us with recreation, beauty, timber and wildlife habitats.

Wastes should be used to build green hills.

Routeways should be designed for all types of user, not just for motor vehicles.

Old towns should be revitalised and new villages made.

In growing food, farmers should conserve and remake the countryside.

Buildings should stop behaving like spoilt brats: each should contribute to an urban or rural landscape.

Landscape architects use the word ‘landscape’, in a professional sense, to mean ‘a good outdoor place’: useful, beautiful, sustainable, productive and spiritually rewarding. To achieve these goals, there is but one necessity: when preparing and approving plans for new places, or spending money on old places, we must look beyond the confines of each and every project.

Gazing at these wider horizons, we can see that too many development projects are initiated by specialists who have been imprisoned within ‘closely drawn technical limits’ and ‘narrowly drawn territorial boundaries’. The technical limits are those of specialised professions, including architecture, engineering, forestry and farming. The territorial boundaries are those of land ownership.

It is not the specialists’ fault or the landowners fault. But if their approach results in narrow-minded single-objective projects, we won’t have the public goods associated with a collective landscape. That’s why society needs more landscape planners and more landscape architects.

Jellicoe identified the making of a collective landscape as ‘the most comprehensive of the arts’ and wrote that ‘We are promoting a landscape art on a scale never conceived of in history.‘

This requires environmental assessment, and some visionary landscape plans. But most of the work is done through environmental impact design, We need to fit land uses together and create collective landscapes. Good landscape planning is a necessary precursor to good landscape design – and the good life.

How should a collective landscape be planned?

The landscape urbanism design method is a good approach because it encourages designers to think of landscapes from the different viewpoints of everyone who will use it, see it and be affected by it. This includes functional, ecological and visual considerations.