The Metropolitan Green Belt and sustainable landscape planning for a greener 21st century London

[Note: there is a longer version of this video below, with more about the history and about the environmental roles of the London Green Belt]

The London Metropolitan Green Belt is under threat from house builders, who prefer building on cheap greenbelt land to expensive brownfield land, and from those see it as a cheap solution to the shortage of housing resulting from London’s expanding population. The Landscape Institute is preparing a Greenbelt Policy Paper and the above video was made as a contribution to the debate, from Robert Holden and Tom Turner. The ten main points are:

- The London Green Belt is widely acclaimed as a popular and successful policy. It should be retained, conserved and enhanced.

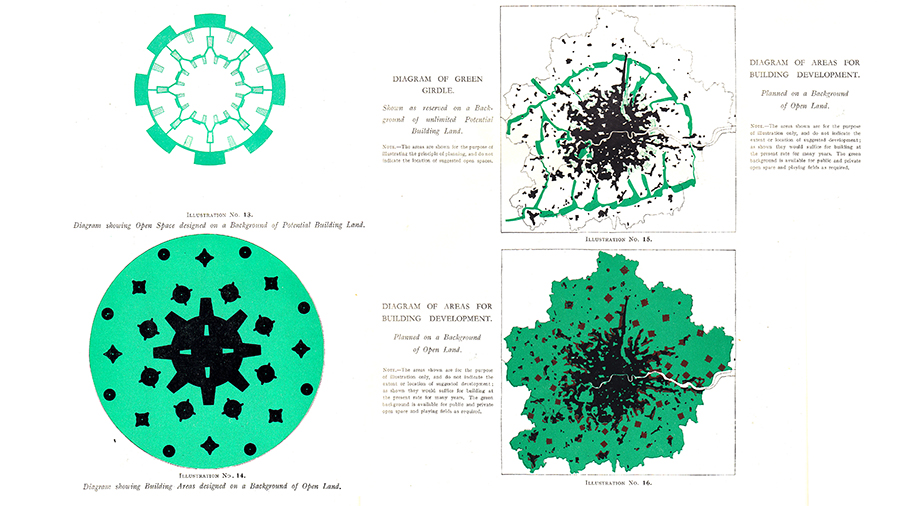

- The video starts by making the point that two roles and two histories underlie the Green Belt idea. First, it is as an idea for restraining the growth of London, which was proclaimed in 1580 by Elizabeth I (William Petty, quoted on the video, gave a statistical argument for containing London but did not specify the width of a protected belt). Second, it is an idea for London to have a country zone for a wide range of green belt uses, including conservation, recreation, food production and water management. John Claudius Loudon (in 1829) and Ebenezer Howard (in 1898) were the main proponents of this idea. Loudon had an instrumental role in the development and adoption of landscape architecture.

- In the 20th century, the Green Belt’s role in controlling the growth of London received more official support than its other roles.

The London Green Belt needs active conservation and enhancement. We recommend:

- Carry out studies of each parcel of Green Belt land (eg following the example of the work Land Use Consultants did on the Coventry City Green Belt) and formulate conservation and enhancement policies.

- Establish a London Green Belt National Park Authority, or similar body, to oversee the London Green Belt and encourage volunteer bodies to help with its management. This can include:

- Land-owning trusts, like the National Trust and the RSPB

- Conservation volunteers undertaking practical work (eg on woodland management, footpath maintenance and collecting litter)

- Pro bono advisory work by landscape architects

[This is a shorter version of the video at the top of the page]

Should the London Green Belt have National Park Status?

We recommend the following objectives for the London Green Belt National Park. They are drawn from government guidance on national park objectives and NPPF green belt objectives:

- to check the unrestricted sprawl of London and safeguard the countryside from encroachment

- to promote sustainable use of the Green Belt

- to promote understanding and enjoyment of the Green Belt by the public

- to enhance the beneficial use of the Green Belt’s natural and cultural heritage, such as looking for opportunities to provide access; to provide opportunities for outdoor sport and recreation; to retain and enhance landscape visual amenity; to improve damaged and derelict land

- to promote environmental objectives including biodivesity, fresh air, combating climate change, soil conservation and water management

The National Parks UK website uses the strapline ‘Britain’s Breathing Places’, possibly without knowing that the term ‘Breathing Places’ was introduced by John Claudius London in 1829 in connection with London’s landscape planning. Loudon did not wish to prevent sprawl but promoted green belts and was very interested in the use of green belt land. The NPPF list of green belt objectives includes biodiversity and should be extended to include a wider range of environmental objectives relating to air, water, soils and landform.

Should the London Green Belt be used for housing?

As mentioned in both the shorter and longer versions of the video, a number of people are making a case for housing development on green belt land. They do so because London’s economic success is causing an influx of people and a continued rise in house prices. One may think, as I do, that it would be better to halt the growth of London’s population. But while its growth continues there is a strong case for asking landscape architects to advise on how the urban landscape should change to meet the demand. The alternatives are:

- Build on brownfield land so long as it is available. Most observers agree that London has a large area of brownfield land and that this should be used before any new land is allocated to housing.

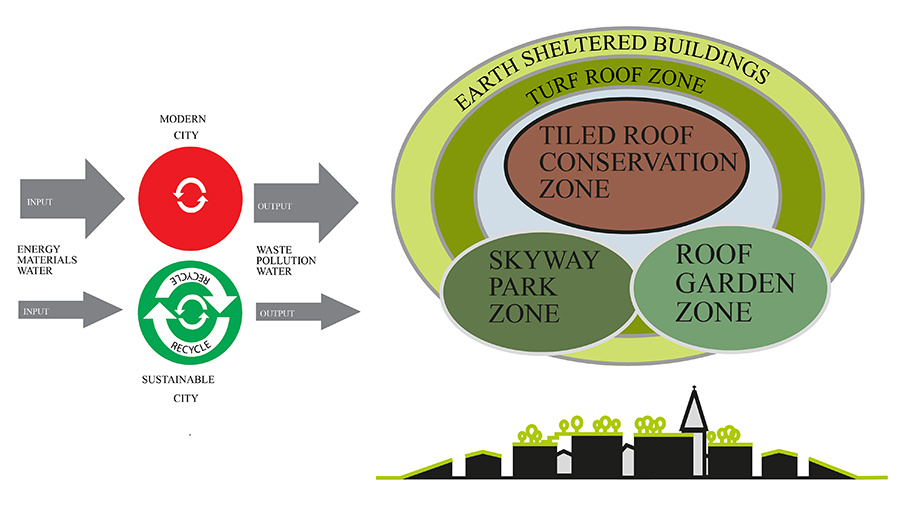

- Raise London’s residential density: Paris has a population of 21,498 people/km2. Greater London has a population density of 4,761 people/km2. Greater London’s density can be raised by building up and by building below street level. London can create a new green landscape by becoming a roof garden city.

- Build on greenbelt land, with the type of consequence shown in the below illustrations, taken from the two videos.

When Loudon, Howard, Unwin and Abercrombie made the case for a London Green Belt they saw London as an unhealthy place to live, because of water pollution and air pollution by coal fires. The 1929 report, which adopted the term ‘green belt’ was sponsored by the Ministry of Health. London was seen as ‘overcrowded’ and in need of ‘decentralisation’.

Environmental opinion has shifted. Simon Jenkins argued, in 2015, that ‘We should be pulling out all the stops to create a green London’. He explains that: ‘If being green means using the Earth’s resources most efficiently, the greenest person in Britain is reading this article jammed in on a London Tube. He or she is going a short distance home to a shared block of flats, then out to a pub or restaurant whose staff, tables and ovens have supplied a hundred meals that day. That’s green. The reality is that the greenest places on earth are cities. The greenest place in Britain is central London, with the most people crammed into the smallest space. They thus minimise the use of transport and energy and maximise the use of buildings and infrastructure’.

The air and water pollution which beset London in the first half of the 20th century were largely dealt with by the start of the 21st century. But London has new environmental problems: motor vehicles are polluting the air and excessive use of drains is causing floods. Luckily, both problems could be solved by green landscape planning:

- water can be detained, infiltrated and evapo-transpired by green roofs and greenways

- greenways and green streets can be used for green transport, without using air-polluting motors

London can and should become a model for the adaptation of its metropolitan area to the green ambitions of the twenty-first century. Its landscape can be re-planned on eco-city principles:

- environmental quality and economic productivity should be raised;

- inputs and outputs of energy, water and materials are reduced.

In short, London needs a Green Belt, a Green Hat, a Green Coat and Green Leggings.

The CPRE calculated that in March 2015 the Metropolitan Green Belt was threatened with the following developments:

1. Bedfordshire: 13,000 dwellings; 121 hectares freight terminal and warehousing

2. Berkshire: 4,000 dwellings in Windsor and Maidenhead

3. Buckinghamshire: Expansion of Pinewood Studios; HS2 route

4. Essex: 9,100 dwellings in Basildon; 2,900 in Brentwood; 2,000 in Castle Point; 1,250 in Epping Forest district; 2,785 in Rochford

5. Hertfordshire: 34,000 dwellings across Dacorum, North Herts, St Albans and Welwyn Hatfield districts; 146 ha railfreight terminal

6. Kent: 450 dwellings near Sevenoaks

7. Redbridge: 2,000 dwellings

8. Surrey: 15,000 dwellings across Guildford, Reigate and Banstead, Runnymede and Woking; hotel and golf course

[The below illustrations show before and after housing images for housing in the green belt, as on the two videos].

Radio 4’s Costing the Earth: Greening the Green Belt held a good discussion of green belt issues Wed 11 Mar 2015 and ended with the same conclusion as the above videos: much could be done to enhance the landscape, recreational and environmental qualities of London’s green belt.

The phrase ‘Lungs of London’, applied to its green public open spaces was first used by Humphry Repton’s patron (William Windham), who attributed it to one of Lancelot Brown’s patrons: William Pitt the Earl of Chatham. Windham used the phrase in a speech in parliament (on 30 June 1808) in which he argued against the crown having a right to build on Hyde Park. Dieter Helm makes a similar point point that selling a building plot in a St James’s Park might raise enough money for a new hospital. Like the Green Belt, ‘it is a public good in economic terms and it does not follow that the economically efficient thing to do’. The question we should ask is ‘How much could we get out of that land if we managed it properly?’

Hansard reported on Windham’s speech: ‘Against the plan he must enter his protest. He was not quite sure that his majesty possessed the right of disposing of the park in the way proposed. It would be a satisfaction to him to know how the crown and the public stood in that respect, and whether it had not given up the right which it was now intended to assert, in consequence of the payment from the Consolidated Fund. It was idle to suppose the plan would not go on if it were once begun, and that it would be limited to eight houses. These, houses would go on, co-operating with other houses, until it would be no longer a park. Indeed, it could scarcely be called so at present, for it was almost invested with houses. On one side there was Knightsbridge, grown into a considerable town; on another, Kensington. There was also a great town starting up on the northern side. Now, if in addition to these a number of houses should be erected, the power of vegetation would be completely destroyed. The park would no longer be that scene of health and recreation it formerly was. It was a saying of lord Chatham, that the parks were the lungs of London. He could devise no means more effectual for the destruction of these lungs than the proposed plan. The great increase of the metropolis might be attributed to the desire which every man felt to get as it were into the country; to go a little further towards it than his neighbour. He had heard of parks being decorated with grottos and temples, but here was a plan to decorate a park with houses; as if a citizen, who should leave Whitechapel on a Sunday evening to get a little fresh air, would feel much gratified when he arrived at Hyde-park to see nothing but houses, he would most probably think that he had seen enough of these in the course of his walk’.

London’s population was 3,188,485 in 1815 and in 2011 the population of Greater London and those counties adjacent to the green belt was 18,868,800. Then as now, it is ‘idle to suppose’ that if a small number of houses is allowed on one part of the green belt ‘it would be limited’ to a small number of houses. Simon Jenkins makes this point on the above Radio 4 programme: ‘At the moment we have to fight every inch of the way because the pressures from property developers to build on those sites is so intense…If you let one bit of green belt go, every lawyer, every planning lawyer hired by every property developer , will say “Ah, that’s a precedent” – and we’re finished. At the moment we’ve got a principle which is that the green belt is sacrosanct’. ‘No one is going to build houses for the poor in the green belt. They’re building executive homes there. That’s what they want to build’.

See also:

- Origins of the green belt idea

- House building on the London Green Belt: would a Grand Bargain make it possible?