The knights of landscape architecture who planned the British New Towns

Thank you to FOLAR for holding a seminar on the landscape architecture of Britain’s New Towns. The above video, which was my contribution to the event, celebrates the contributions of the Four Landscape Knights (Sir Patrick Abercrombie, Sir Frederick Gibberd, Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe and Sir Peter Shepherd were members of the ILA, two of them as Presidents of the ILA) and ends with my observations:

- the new towns were very successful at the large scale of landscape planning and at the detailed design scale

- but the new towns were disappointing at the intermediate scale of site planning

- the landscape architecture of the new towns was much better than other town development projects of the same period.

Concepts from the history and theory of landscape architecture also had a profound influence on the planning of Britain’s Garden Cities and post-1946 New Towns:

- low density housing with private gardens – ‘a villa for everyman’

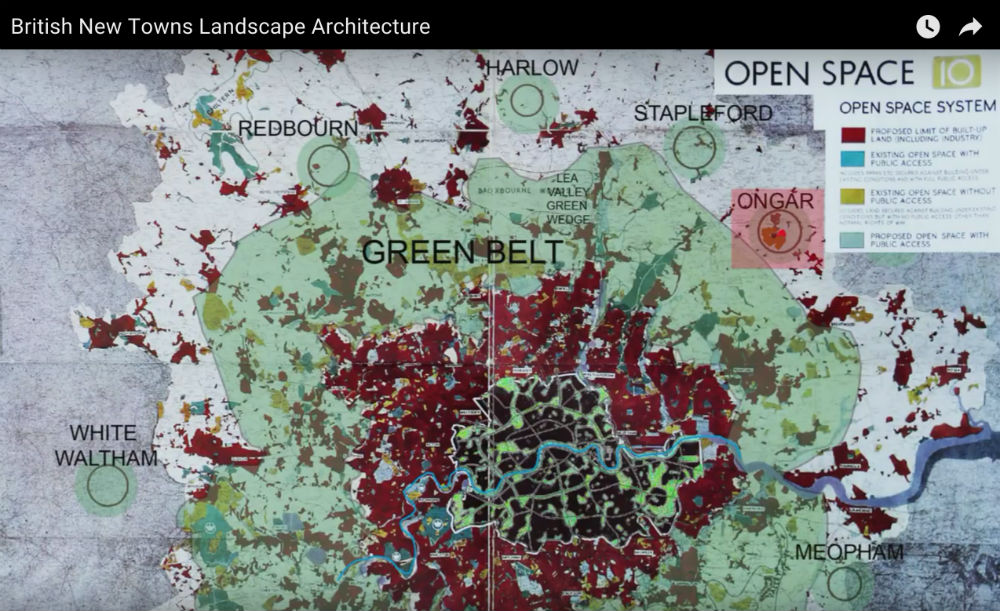

- the use of green belts to control urban sprawl, both outside London and beyond the boundaries of the designated new towns

- the use of open space networks to separate neighbourhoods within the boundaries of the new towns, while also providing land for parks, footpaths and cycleways

The video includes:

- a sketch of the 19th century origins of the landscape concepts used in planning the British new towns

- video clips of Patrick Abercrombie explaining these ideas, as part of the 1943-4 County of London and Greater London Plans

- video clips of Frederick Gibberd and Geoffrey Jellicoe explaining the landscape planning of Harlow New Town and Hemel Hempstead New Town

Peter Shepheard has the rare distinction of having, effectively, designed 32 British New Towns by the age of 30. Shepheard was born in 1913 and worked on the London plans in 1942-3. Ongar, a sample new town which Shepheard designed for the Greater London Plan, determined the landscape planning of all 32 new towns.

The Landscape Institute should join forces with the Town and Country Planning Association to argue for the re-activation the 1946 New Towns Act. It is a much better policy than encouraging the creeping expansion of our villages, towns and cities onto green belt land.

One point that struck me about the conference was the discussion raised at the end in a question by an economist: why the absence of statistical measurement of success and failure of the work of landscape architects? This I suspect touches on something that landscape architects veer away from: statistical discussion.

This is most visible in current British practice in Landscape Character Assessment. But was also evident in the discussion at Reading in response to the question. Landscape design is an art form was one response (as if there was no statistical analysis in fine art criticism, which is not longer the situation by the way). Wishy washy was the general response.

However, the point surely should be that the applied art of landscape architecture is open to rigorous statistical analysis. Embodied carbon embodied energy, species diversity, biomass, aspect and openness to sunlight, wind shelter, etc. are all open to measurement.

Similar social sciences have indicated ways of measuring human satisfaction, and happiness, and crime rates are measurable. While property developers regularly measure capital values and economic return. No business park developer would dream of letting building contracts without calculating the service charges required to maintain property and an estate in the long term.

Another curiosity about landscape architecture generally is why it does not exploit sufficiently the one tool that landscape architects have devised to digitally record topography. How many British landscape architecture courses now teach GIS? Greenwich I am told has terminated its teaching in the Masters and Diploma. Why?

It is possible to measure landscape. Why do British landscape architects not do so?