Carl Steinitz: On the Future of Landscape Architecture

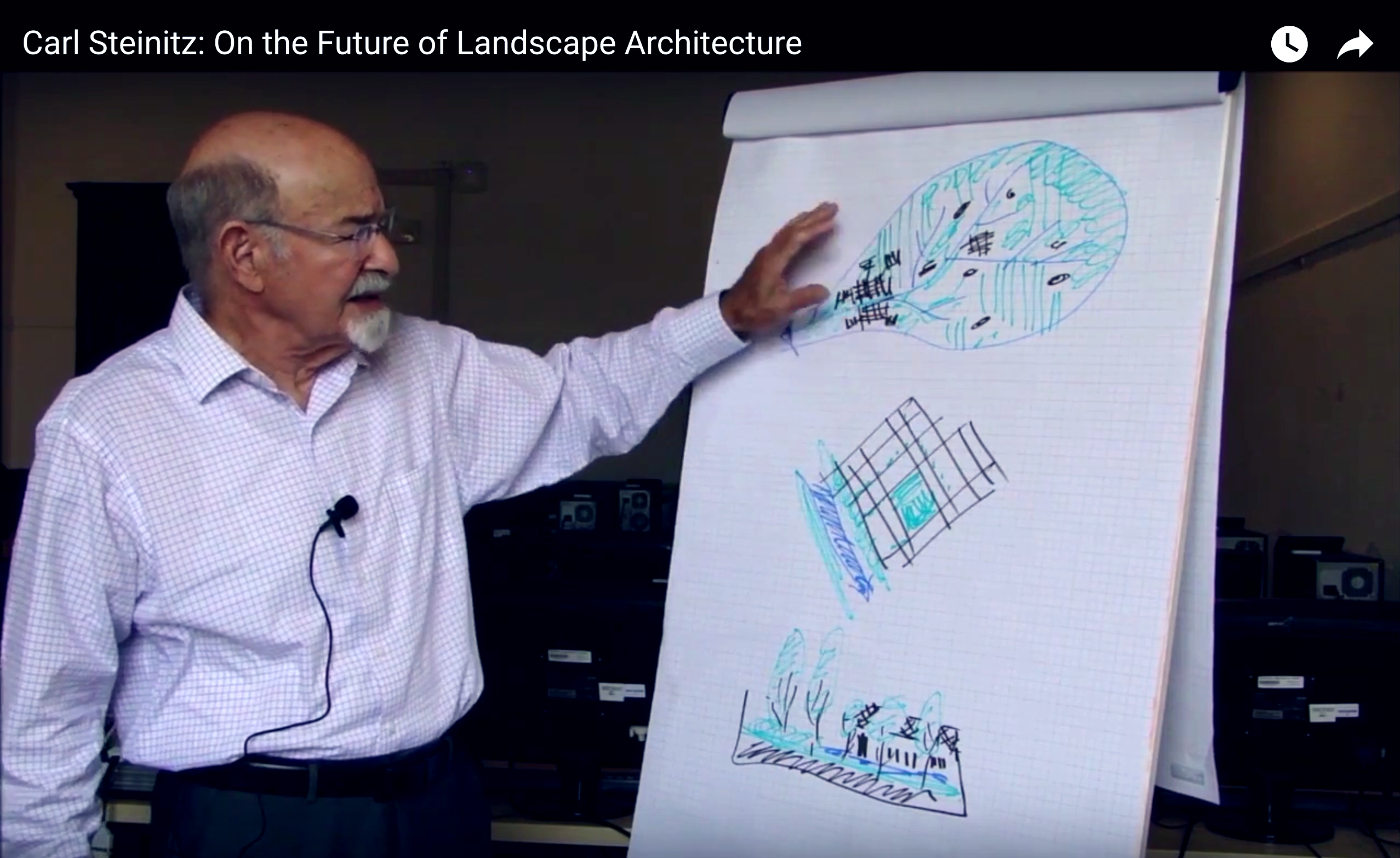

Steinitz has worked at the intellectual heart of landscape architecture for half a century. In this 2016 lecture, he uses a single illustration to discuss The Future of Landscape Architecture. It shows three design scales: the garden, the park and the city. This helps him make points about the profession’s history:ues occur in the world’, including differences in poverty, growth, bad water and lack of food. Issues relating to the garden scale are ‘nice but less relevant’.

- The relative emphasis on the three scales has changed

- Before the name landscape architecture came into use [in the 1860s] there were people like Peter Joseph Lenné and John Claudius Loudon who worked ‘across these scales’. So did Frederick Law Olmsted and Warren Henry Manning after the profession’s foundation. They worked in different ways at the three scales.

- In the 1920s the money was at the garden scale

- In the 1930s the medium and large scales came to be called planning and were taken over by planners. The small and medium scale became ‘the territory of landscape architects’

- In the 1960s, when Steinitz, began teaching at Harvard, landscape architects like Ian McHarg and Phil Lewis, resumed the profession’s involvement with the large scale

- In the 1970s most landscape architecture activities moved ‘back down’ to the medium and small scales and treated ‘design and planning as different things’

- In the 1990s there was a frontal attack on the small and medium scales by architects. Barcelona (the 1992 Summer Olympics) ‘was a huge event in this’, with architects designing gardens and parks (as did landscape architects).

- In recent years, landscape architects have been interested in moving back to the large scale – because this is the scale at which real issues arise.

Looking to the future, there are four major options

- Landscape architects could concentrate on the small scale,

- The landscape architecture profession could disappear, with the work being done by architects, engineers and geographers

- We could retain the ‘very foolish idea’ that there’s a difference between planning and design. It is foolish because all the scales are ‘design’ in the sense of proposing potential change.

- Instead of starting with teaching about small projects and working up in scale, we should start at the large scale of real issues and work down. The fourth option is to see the profession in the way the founders of landscape architecture saw it. We should be prepared to practice, in different ways, at each of the scales: collaboratively at the large and medium scales and individually at the small scale.

There is no reason why landscape architects should see themselves as the stewards of the landscape , or as the protectors of the landscape, or as the designers of the landscape. We are not the only ones with wisdom at any of the design scales. So we should concentrate on the scale at which society needs us the most – which is the large scale. ‘That’s my view’.

Comments

Readers will not be surprised to learn that the author of a book on Landscape planning finds himself in 70%+ agreement with Carl Steinitz. He does not mention GIS or Geodesign in the above lecture but I also agree about its importance and put a GIS diagram on the cover of my book.

- Urban and landscape planning are, and should be, at the heart of our work. But I see a focus on public goods as giving more definition to this work than the issues of scale and collaboration (which Steinitz uses).

- In the UK an increasing proportion of the small-scale work is being done by garden designer, who have a focus on private goods. Architects are more interested in competing for the medium scale work in which they have no training and little skill.

- Steinitz is right that design is the crucial skill at all three scales. But what do we design? The term ‘landscape’ needs to be explained and this should be done by saying that we compose ‘landform, water and vegetation with buildings and pavings’. This is true each of the three scales.

- I agree about the importance of Loudon to the history of landscape architecture but also think the history of the art pre-dates London by at least 5000 years. The landscape profession’s lack of interest in its pre-1860 history is a major cause of its failure to explain itself and understand itself.

- I agree that use of the term ‘stewardship’, by both the ASLA and the LI is misleading and should be dropped.